#4: How I Regularly Kick the Algorithm in the Balls

Why artists should periodically alienate their social media followers on purpose.

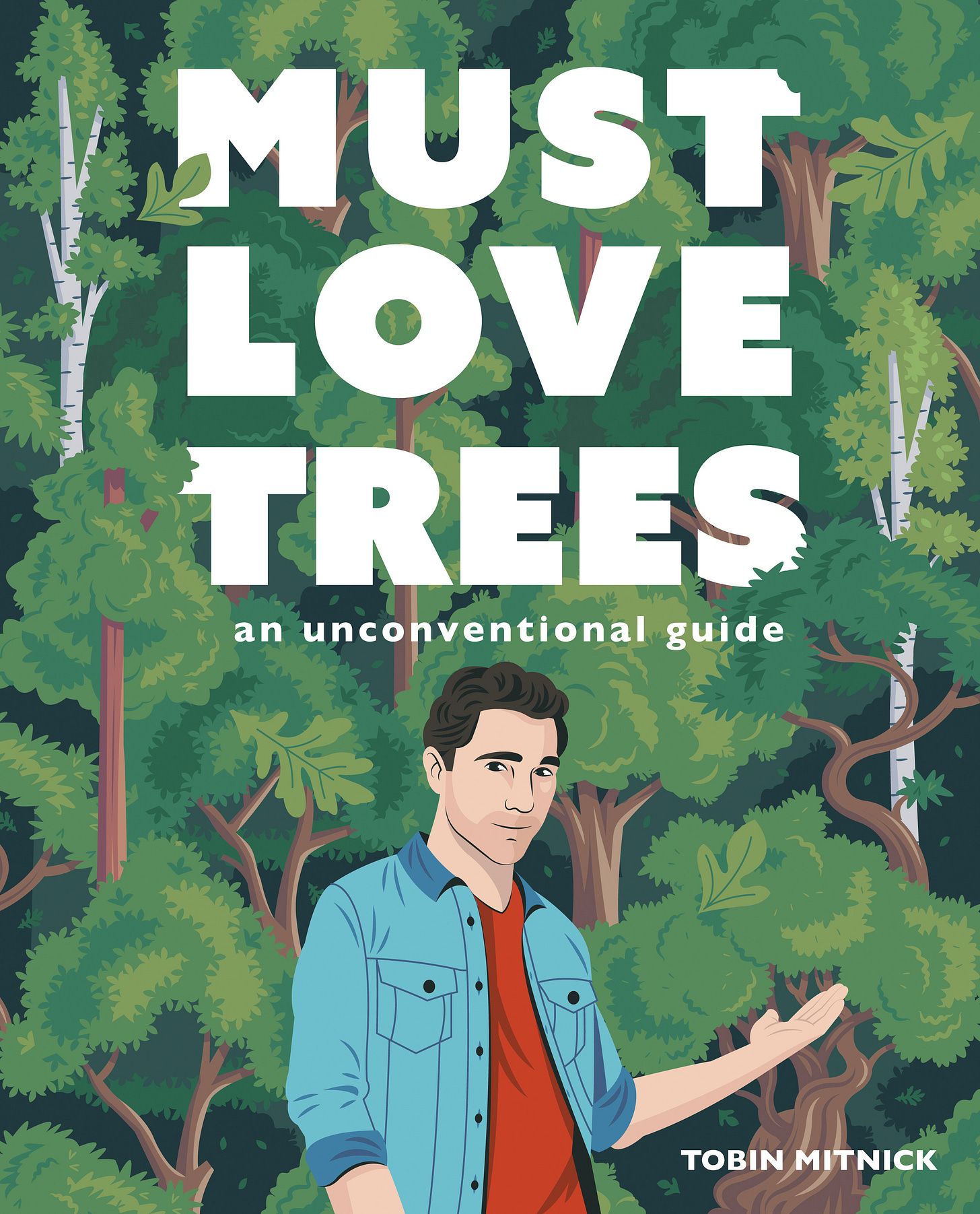

Another week, another shameless plug for my book, Must Love Trees: An Unconventional Guide. It makes a great last-minute holiday purchase for that Jew or Gentile in your life who expects their gifts to come four months later. Don’t delay. P.S. the Dummy Book Giveaway contest is still on-going! Send proof of purchase to MustLoveTreesBook@gmail.com with subject “Tobin is a Dummy” to get a chance to win my filled-up dummy book at the end of the pre-order period.

Trees Future: Why I regularly kick the algorithm in the balls

If you think of yourself as an artist, I recommend regularly kicking the Algorithm square in the balls. This probably does not mean what you think it means. Here’s a few videos where I’ve tried to do it.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Notice anything different? That’s right—these videos aren’t particularly tree-centric (and neither is the rest of this post, sorry.)

It’s really important for me to think of myself as an artist, but it’s very difficult to maintain an identity of being an artist when your medium is social media because you sometimes feel like you’re being driven, as opposed to being in the driver’s seat, creativity-wise. I’m not reinventing the wheel by saying that. But there is an exercise that I engage in roughly once every month in order to re-orient myself as the guy in charge here, as opposed to, say the “Algorithm”:

I kick the “Algorithm” square in the balls.

What do I mean by “algorithm,” “kick,” and “balls”? First thing’s first: let’s define the Algorithm.

The Algorithm is an amalgamation of the Matrix and the characters in “Inside Out.”

The Algorithm is a room. There are fifteen people in it (Andrew, Fabiola, Mark, Melissa, Heidi, Bridget, Mel, Harry, Zak, Annemarie, Jane, Stevie, Lou, Eduard, and Bruiser) pulling particular levers meant to prioritize particular things on each social media platform—funny things, sad things, profound things—in order to maximize engagement and drive up ad revenue. They’re all the best in the biz, and they know just what kind of content to prioritize each day, each hour, each minute, in order to make that happen.

Every time someone says, “Hmm. The video didn’t go viral with just one. So, next time, I’ll interview two Giant Sequoias,” Eduard gives a fist pump. Whenever someone says, “I hate this thing. Guess I gotta take my shirt off,” Annemarie gives a thumbs up. And whenever someone thinks, “it’s December and holidays are on-trend, so I’ll buy a Christmas tree, hang it with Menorah ornaments, then sing a Kwanzaa song while standing on my head. Without a shirt on,” Zak makes a note, Stevie runs the data, Fabiola gives the command, and Bruiser pulls the lever. Because the common feature of all these “strategies” as we might call them, is the user’s aim of getting engagement from the public. And that’s keeps them making more stuff and coming back again and again.

So whether we’re complaining about the algorithm, or reveling in its spotlight, or trying to outsmart it, or trying to predict it—these are all versions of obeying the algorithm. Because we are always centering the idea of engagement volume. Which keeps us coming back to the platform. Which drives up ad revenue.

That is what the algorithm is.

So how do I “kick” the Algorithm square in its “balls”?

Here’s where it helps to elaborate on what I meant when I said “I think of myself as an artist.”

(Note: I’ll be discussing my personal definition of the term for myself, so no need to get into nonsense rhetoric wars and lose the thread before we start some serious ball-kicking. Thanks.)

I have somewhere in the vicinity of 400,000 unique followers across social media. It’s given me much more visibility and recognition than I had in my previous life solely as an actor and comedian, even when I was the lead in a movie. Prospects are, understandably, much better career-wise on this “tree guy” off-ramp that I’ve made for myself—hopefully I’ll sell this book well that I’m proud of, then hopefully I’ll get someone to buy it, and then hopefully I’ll get to keep doing what I’m doing, except better, in the company of actual people, and make a living off of it. I love trees, and they are continuously energizing for me.

But I still audition for film and television, because I still consider myself, first and foremost, an actor and an artist—a person who has autonomy in what they create. Someone who says, “I’m the boss here. I do things that I find funny or beautiful or profound, and I put them out into the world because I hope the world loves them as much as I do.” Then you walk out of the damn audition room, throw your damn script in the trash, and you don’t give it any more of your damn precious energy. Pride is my power as an artist: I gave you my version. Great if you liked it. Too bad for you if you didn’t. There are other aspects: collaboration, logistics, self-promotion. But it’s all pretty empty without the pride at the center.

And when I give up my pride—when I become someone whose online behavior has constantly been edified and streamlined by algorithmic feedback that tells me what is good and what is not by a simplified measure of popularity—I feel I am no longer an artist. When I let the work I do be dictated by a need for public approval, my autonomy goes poof. Then what I make becomes predictable and stale because it’s based on trying to anticipate what other people want. That’s the moment when I transform from an artist to a content-creator who works in customer service.

Now this isn’t about right or wrong. Customer service is a huge part of social media for many people. They depend on it for their business. It makes perfect sense to tack this way for them. It would probably be a terrible idea for them to try to kick the algorithm square in the balls.

No: this is about how I see myself. And if I’m an artist on social media, it shouldn’t scare me to take some risks.

And one of the most basic risks one can take is to lose some followers.

This is frightening for most people, because, regardless of how petty it may seem on the surface, losing followers hurts. I remember seeing some piece of journalism years ago about CEOs who make bajillions of dollars and were given only a tiny pay cut, then lost their minds and became depressed as a result. Not because they needed the money, but because they began to equate number of dollars with self-worth. Likewise, no one really needs all their followers—my existence would be essentially unchanged if I lost most of mine—but it’s painful all the same because users of social media have been conditioned to feel that way.

And every time you shed a tear for followers lost, everyone in the algorithm room lets out a huge cheer, because what they are doing is working. You are engaging emotionally. You will return to get those followers back. Revenue will go up. The Algorithm triumphs once more.

So my advice for artists this holiday season is to roundhouse kick the algorithm square in its ever-loving nutsack.

And here’s how to do it:

Have fun making something absolutely terrible, quality-wise, then post it. Or post something completely off-topic compared to what your “brand” is, because you find it fascinating and cool. Or something loud and weird, because you think it’s hilarious. Or something silent and baffling, almost off-putting and mesmerizing in its stillness. Anything that you love that other people will absolutely not expect and probably be weirded out by.

(I can’t tell you exactly what to do, because you know best what gets engagement on your platform. So figure out what is 100% perpendicular to that, make it, and post it.)

It should be your absolute goal to alienate people.

(Also, we’re obviously not talking about sharing some political opinion or culture war contrarianism or something intentionally controversial. That stuff gets engagement, and it plays straight into the hands of the people in the Algorithm room. Big yawn to that.)

I’m talking about something that makes you alone sad or happy, some idea or video that you’d really like to show people, despite the fact that it isn’t aligned with how you might be perceived.

When news of this material hits the Algorithm room, they’ll be baffled. Heidi will mash buttons. Lou will throw his vanilla latte into the air in exasperation. Melissa will simply vomit. All of this because they can’t understand why you did something that wasn’t trying to please them. And for a millisecond, the room that makes us all want the same thing will be thrown into complete disarray by you saying that the Algorithm Room does not matter.

Hopefully, your audience will hate what you make. Your mom might call you and ask if everything’s alright. At least a few people will stop following you. The vast majority of people will ignore you. And a few people will absolutely adore you because you showed them something completely different from usual that they happened to find compelling.

And you will feel great. Because for one day, you were able to do what good artists can do, at least to my mind: you made something you loved for whatever reason, then showed it to people, then dropped the mic. Even if the mic wasn’t on in the first place.

Kicking the algorithm in the balls is a palate cleanser. It’s a small rebellion. It’s a mitzvah. It’s a moral act. You can take back your autonomy as a creator, if just for one an hour.

Then, one day, out of the blue, you’ll get a message like this:

“My husband who has alzheimers totally cracked up when he saw this video. So, thank you for bringing some joy into the life of a man who finds everything confusing. And to his wife who doesn't get to see much spark in his eyes any longer. What probably started out as a silly moment for you turned into a huge blessing for us. Thank you.”

Those are the rare messages I treasure, and those are the ones that somehow only arrive when I’ve made something in service of myself and itself. Here’s the video that elicited the comment:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Great if you liked it. Too bad for you if you didn’t.

Trees Past: Death of an Icon

Tragically, it seems that my Ficus Benjamina, which I collected from my friend Emily’s yard in summer 2021, is going the way of the dodo:

It’s a very large tree in terms of collection, and I think it simply wore itself out in terms of producing new growth—it was almost psychotically productive during its eighteen months in a pot and I don’t think I gave it enough sun to keep up with its ridiculous rates of photosynthesis on its transition to a new yard when I moved a couple of months ago. Tropical trees like ficuses are tough mudders, but man, I wish I’d given it more sun.

I used it in a short series project that I ended up abandoning, where it was a stand-in for Emily’s past relationship. That project was called “Tree Therapy,” and I very much liked it, despite the fact that I don’t think it was a bit over-earnest and not really viable for more than one episode.

Trees Present: Playground Trees

Every time I pop into Beeman Park in Studio City, CA, I’m so grateful for these two enormous Ash trees that they have growing in the center of their playground. I’m not sure what species they are exactly, but they’re just about as big as ash trees get. One of them (not the one pictured above) is about twenty feet in circumference.

Large, centrally placed trees are good for playgrounds. Kids love congregating around them. I love congregating around them. All playgrounds should be designed with a spot for an enormous tree to flourish in its center. Sets the right tone.

On a side note, I’m curious as to whether Ash, which grows so well and commonly in Los Angeles, will meet the same fate as its East Coast cousins, which are currently being decimated by the Emerald Ash Borer.

An Out-of-Context Sentence from Must Love Trees: An Unconventional Guide

Page 114:

“The mountain hemlock looks simply divine as it makes continuous ‘fight me’ gestures.”

Pre-order from:

Things I am reading and thinking about this week: